- Home

- Nigel Kneale

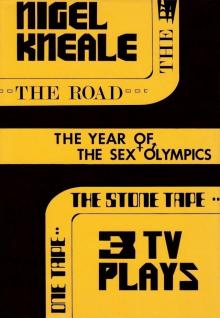

The Year of the Sex Olympics and other TV Plays

The Year of the Sex Olympics and other TV Plays Read online

BY THE CREATOR OF QUATERMASS

Three of Nigel Kneale’s science-fantasy plays for television are here published for the first time. Author of the pioneering “Quatermass” serials, Mr. Kneale shows here the same mastery of suspense and unrivalled ability at employing science fiction and supernatural themes in TV drama.

“The Road” is set in 1770 and concerns the conflict between an early scientific investigator and a philosopher as they come face to face with terrifying supernatural phenomena in a haunted wood.

“The Stone Tape”, surely one of the finest of 20th century ghost stories, also concerns the scientific investigation of a haunting, this time by a modern electronics research team at their newly acquired headquarters, an ugly Victorian mansion built on even older foundations . . .

The title play, in sharp contrast, is concerned entirely with the future and, in particular, that of television. Mr. Kneale envisages a “cosy and comfy” highly automated society when the problems of war and over-population have been successfully overcome by “Apathy Control”. “Low-drive” people (the bulk of the world’s population) spend their waking hours watching TV and such shows as Sportsex and the Hungry-Angry Show, produced by the “high-drive” personnel of “Output”. With relentless build-up of suspense, “The Year of the Sex Olympics” describes the discovery of a new breakthrough towards better apathy control. A controversial play when first shown in 1969, its underlying thesis—the addictive power of TV—is still being hotly debated and it remains a most vital contribution to the literature of modern communications.

3 SCIENCE-FANTASY TV PLAYS - - - -

THE ROAD

“Stimulating playmaking and the best drama television has offered for many months” —Daily Mirror

“As obsessive, well-argued and worrying as all the best science-fiction aims to be” —Sunday Telegraph

THE STONE TAPE

“This supernatural thriller by Nigel Kneale is one of the best plays of the genre that he has written. Its virtues aren’t just the main spine of the story but the way the characters shift as in real life, the bitter, comic conflict between pure and impure science” —Evening Standard

THE YEAR OF THE SEX OLYMPICS

“A brilliant BBC-TV play by Nigel Kneale, ‘The Year of the Sex Olympics’ carries the concept of addictive TV-viewing to its ultimate—and horrifying—conclusion” —Newsweek

“A riveting, brilliant play. Nigel Kneale, who wrote it, deserves placing alongside Orwell as a prophet” —Birmingham Post

“Probably the most profound statement yet made on the box itself about the ultimate impact of television upon our society” —Milton Shulman, Daily Express

“A highly original play written with great force and making as many valid points about the dangers of the future as any science-fiction work I can remember—including ‘1984’ ” —Daily Telegraph

“The most extravagantly good thing. Really good thing. Really. Am I making myself clear? Possibly not. ‘The Year of the Sex Olympics’ was, in its own vocabulary, jumbo-size, super-king” —Sun

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

TOMATO CAIN and other stories (Collins, 1949)

THE QUATERMASS EXPERIMENT (Penguin Books, 1959)

QUATERMASS II (Penguin Books, 1960)

QUATERMASS AND THE PIT (Penguin Books, 1960)

Copyright © 1976 by Nigel Kneale

FERRET FANTASY LTD.,

27 Beechcroft Road,

Upper Tooting,

London SW17 7BX.

Tel: 01-767 0029.

ISBN: 0-904-99709-X

Printed in Great Britain

CONTENTS

Introduction

The Road

The Stone Tape

The Year of the Sex Olympics

About the Author

INTRODUCTION

I find it hard to think of these three television plays as science fiction. My primary interest was in the characters, in developing them as real people. In each case they were faced with some extraordinary situation, of course, but they had first to be brought alive and rendered actable.

“The Road” is a ghost story set in the 18th century and I have tried to place its characters firmly there, in the Age of Reason. One of them is a sub-Johnsonian iconoclast of the London coffee houses, complacent in his vision of a perfectible future. His despised rival is a country squire, an amateur of natural philosophy, whose meek but insatiable curiosity makes him the prototype of the socially irresponsible scientist. Neither man is quite so simplified as that, of course. Each is full of confusions and contradictions. The idealist is also a sensual bigot; the would-be scientist has yet to cast off superstition. But between them these two possess the strands of thinking that will lead to some of the horrors of our own time.

“The Stone Tape” was written as a ghost story for Christmas. If a major electronics company takes over a Victorian mansion as a research centre and finds it indubitably haunted—well, who would be better equipped to crack the phenomenon? At first it is almost a game, a welcome distraction that appeals strongly to the schoolboyish side of the research team. But very soon the joke turns sour.

“The Year of the Sex Olympics” I wrote in 1968, when both technological development and expansion of birthrate were seen to be accelerating almost vertically upwards. As in former ages the classic signs of a disintegrating civilization were starting to show: the excessive obsession with sex, the rat-maze hysteria, the blind fear of the future and numb wish to exchange it for a bleak but at least comprehensible Dark Age.

So—an extrapolation: the New Dark Age brought on deliberately, with the most humane intentions. A world society fed, warmed and protected from its own impulses like so many battery fowls, kept to manageable numbers not by disaster or extermination but by gentle discouragement—by flooding it with powerful vicarious experience, particularly the sexual. The means to do it would be television itself, vastly developed, a non-stop drench of pseudo-experience, irresistible to the senses and quite overpowering. Numbing rather than rousing. Television and pornography in ultimate combination.

It would be a re-stratified world, sorted into the apathetically spoonfed billions who are stunned into the contentment of merely watching—and the tiny live minority who put the show on. It is only this latter group that might still throw up exceptions, odd ones who wish to opt out. And once in a while they might be allowed to do so—at the price of becoming part of the show.

NIGEL KNEALE, January 1976

THE

ROAD

THE ROAD

CAST OF CHARACTERS

SIR TIMOTHY HASSAL ... James Maxwell

LAVINIA, (his wife) ... Ann Bell

GIDEON COBB ... John Phillips

JETHRO, (Cobb’s servant) ... Clifton Jones

SAM TOWLER ... Rodney Bewes

TETSY ... Meg Ritchie

LUKEY CHASE ... Victor Platt

BIG JEFF ... David King

PRODUCER ... John Elliot

DIRECTOR ... Christopher Morahan

Produced on BBC Television, September 29, 1963

THE WOODS – A CLEARING

It is approaching dusk of an autumn day. Leaves are turning brown on the crooked oak branches. A distant owl hoots. The camera tracks slowly forward.

The owl hoots again, closer.

The camera pans suddenly, to a close shot of a frightened man. He is a young countryman in coarse woollen shirt and leather jerkin. His eyes search the darkening trees. His hands are working feverishly to bind two twigs together with strands of grass, into the rough shape of a cross.

A dog barks somewhere nearby. He turns to look in

that direction, grateful for the familiar sound.

THE WOODS – SOME HUNDREDS OF FEET AWAY

The dog barks again, close at hand.

Here a group of men are at work. Four of them are knotting stout ropes taut between the tree trunks to form a line that leads away out of sight, a couple of feet from the ground.

All are countrymen, roughly dressed.

And now another comes, his whiskered face topped by a tricorne hat. He is wearing a cast-off coat of the squire’s, for Lukey Chase is one of the squire’s servants and in charge of the work here.

He is followed by a lad with a sack, from which Lukey is selecting metallic oddments to hang on the ropes—old bells, jangling bits of harness and chain, scrap from a rural forge. Lukey tests the effect as he approaches, tugging at the rope.

The ironware clatters and jangles behind him all along the line. As he reaches the men working on the ropes, one of them turns to him—a huge fellow with a broad, beaming, gap-toothed face.

BIG JEFF: Hey, Lukey—you’re gettin’ a bit of a tune in it now!

Grunts of laughter from the rest. Lukey dissociates himself from the scheme.

LUKEY: I be just doin’ what squire showed us.

BIG JEFF: Sort o’ tune as spooks’d take to, I’d say. He reckon to charm ’em out, hey?

LUKEY: You heard what he said, Jeff. (To the lad) What you got left there?

He delves in the sack and finds a rusty cowbell.

BIG JEFF: I only heard ’un say he were after spooks.

The mock-solemn faces of the others nod agreement.

LUKEY: Squire reckons to stop anybody comin’ through here in the dark without us know.

He attaches the bell to the rope.

BIG JEFF: Ah, spooks’ll just pass clean through a rope. Don’t he know that? Pass through anythin’, a spook can. Don’t even tickle him.

LUKEY: ’Taint spooks he’s settin’ this up for, Jeff, it’s jokers. We got plenty o’ them hereabouts.

BIG JEFF (shaking with laughter): Oh, ah?

LUKEY: Any tricky lad come boltin’ through ’ere tonight—he’ll set this lot off an’ we’ll have him. Now it’s time to finish. Just take it as far as that thorn thicket and we’ll go. (As they move) Hey, where’s young Sam?

BIG JEFF (pointing): There, look. Just went off by his self.

LUKEY: Young devil . . .

BIG JEFF: Beckon he’s frikkened?

LUKEY: Frikkened o’ squire, more like, for makin’ it all up.

He ducks under a branch and makes for where Jeff pointed.

THE CLEARING

Sam is standing where he was, still listening and watching for something.

A wider shot shows this as a small clearing. In it is a fallen tree, a grotesque lightning-seared ruin with one end torn open. It is covered with flat plates of fungus.

There is a tiny squeal a short distance away in the darkening undergrowth. He starts, with the twig cross clutched to his chest. The thin sound is drowned by a series of sharp screeches that move rapidly away.

Lukey appears through the branches at his side.

LUKEY: Killin’ early tonight, that owl.

SAM: Ay.

LUKEY: An old rat squealin’ there . . . make some folk frikkened, they dunno what it were.

SAM: I know them noises. ’Tweren’t like I heard that other time.

LUKEY (scrutinising him): Ay?

SAM: Lukey, I don’t want to come back here tonight.

LUKEY: Tell that to the squire. Come on now . . .

THE ROPED TREES

The lad has strung the last scraps of chain and iron on the completed barrier. Men are picking up their bundles and coils of rope as Lukey and Sam join them.

BIG JEFF: Hey, Lukey . . . reckon we all get a free drink on this?

LUKEY: Squire’s promised it.

Grunts of approval as they start to move off.

BIG JEFF: I’ll say this for squire. He may be soft in the head, but he’s open in the hand . . .

They hurry off along the track. One of them whistles and calls to his dog.

OUTSIDE A TAVERN

The last glow in the sky picks out an inn sign: “The Three Companions”, pictured as a donkey, a dragoon and death, walking arm in arm.

The camera pans down. The windows of the tavern are lit. Outside the front door stands a large four-wheeled handcart with a long shaft. It is loaded with wooden boxes, planks and lanterns.

Beside it are two men.

One of them, in the decent dress of a rural gentleman, is Sir Timothy Hassall, Bt, squire of the district—tall and nervous, his face sensitive and uncertain. He lifts a wooden box from the cart and as he turns with it, the other man, a servant, makes to relieve him of the burden. But he is not to be trusted with it.

Sir Timothy makes for the tavern door, carrying the box carefully.

INSIDE THE TAVERN

The tavern is a crabbed little old place, no more than an occasional halt for passing coaches. Its customers come from the surrounding village, and there are half a dozen of them in the bar now, men in smocks or jerkins exchanging the days slow gossip over tankards of ale.

They watch Sir Timothy pass through with his box. One man with his back turned is nudged out of the way by a neighbour.

MAN: Oh . . . sorry, squire.

SIR TIMOTHY: No matter, Gibbs. No matter.

He has almost reached the door of the private parlour at the back when it flies open. The landlord, a harrassed, grizzled man, emerges in a hurry.

SIR TIMOTHY: Careful!

LANDLORD: Beg pardon, squire! (Confusedly) I’ll just get the logs.

SIR TIMOTHY: Logs? Surely I need no logs.

LANDLORD (nodding at the private room): He wants ’em!

A deep-throated roar from the room sends him on his way.

GIDEON COBB (off-stage): And brandy, landlord! Quick, now!

LANDLORD: Yes, sir.

Sir Timothy disappears into the private room, closing the door. The landlord hurries behind the bar and shouts to his daughter, Tetsy, the ugly-pretty girl of 18 who is serving ale there.

LANDLORD: Where’s Jack? (She shrugs) Devil take him! Brandy then—quick! I must go for logs.

He shuffles out through a dark open doorway behind the bar and can be heard thumping about there and cursing.

Tetsy finds the brandy bottle, looks for glasses. There is a ripple of renewed interest among the villagers.

FIRST VILLAGER: Makin’ your ol’ daddy jump, girl! (A nod at the private room) Who is he?

TETSY: Mr. Cobb.

FIRST VILLAGER: Who’s Mr. Cobb, then?

SECOND VILLAGER: Friend o’ squire’s.

FIRST VILLAGER: I can see that, but . . .

TETSY: He got off the London coach.

She polishes glasses.

SECOND VILLAGER: I seen ’em—him an’ his black man.

FIRST VILLAGER: Black man?

TETSY (sharply): Shhh!

The door of the private room has opened. A tall negro is standing there. He is impeccably liveried as a gentleman’s personal servant. His manner is cool and dignified. He calls in a voice that carries both culture and authority.

JETHRO: Where is the brandy for my master? (Seeing Tetsy with the bottle and glasses) Bring it.

She manages to nod, and he goes back into the room. She is plainly terrified.

TETSY (whispering): My mam says black men come from the Devil.

SECOND VILLAGER (grinning): He comes from London. Same thing, eh, Tetsy?

FIRST VILLAGER: ’Tis the fashion there, they say, to have a black boy in yer house, dressed up like a great dolly. All the rich men got one. An’ ladies too!

Tetsy has brandy and three glasses on a tray. She calls into the dark doorway.

TETSY: Father, I’ve got the brandy.

LANDLORD (off-stage): Take it in, then.

TETSY: Eh? Me?

LANDLORD (off-stage): Yes, you!

Trembling, Tetsy makes for

the private room and knocks. The door opens immediately and there is Jethro’s face a foot from her own. She nearly drops the tray.

INSIDE THE PRIVATE ROOM

There are three people in the private room. Sir Timothy is standing by the table, using what part of it is not covered with food to display the apparatus he has brought in—a couple of weirdly-eccentric, lop-sided jars with stubby off-shoots of tubing and stoppers, not unlike alchemists’ alembics but with heavy, domed lids added.

He also has a crude electroscope in an ornamented case. Some of its internal parts are made of small bones, and it is topped with a mummified cat’s head with whiskers.

Behind sits his wife Lavinia in an elegant riding habit. She is something of a beauty, not much over 20 and ambitious. Her clothes are London fashion. So is her imitated, malicious smile.

But dominating the room is Mr. Gideon Cobb. Bulky and ugly, he carries himself with style. His fleshy face is neatly shaved and laced about at the neck. His clothing is plain but characterful in contrast to the absent-minded dullness of the squire’s. It seems designed to set off the pugnacious force of his expression. He is a man accustomed to dominate, and takes it for granted that his hearers enjoy the experience.

Many of them do.

He now has a collection of used plates in front of him, the remnant of a steak pie and an empty pudding bowl, with coffee jugs and cups. He is still gobbling spoonsful of pudding from a plate, while Sir Timothy tries to explain his apparatus.

SIR TIMOTHY: . . . and in jars like this I’m hoping to secure samples of the imponderable fluids which, if I am right . . .

Cobb swings round in his chair to shout through a mouthful of pudding.

COBB: Where are those damned logs? Send him in with them! I’m dying of cold.

Tray of brandy in hand, Jethro turns to disclose the girl in the open doorway. Seeing his mistake, Cobb guffaws.

COBB: Ah, my dear! Thought it was your villain of a father.

TETSY: He’s getting the logs, sir.

The Year of the Sex Olympics and other TV Plays

The Year of the Sex Olympics and other TV Plays